|

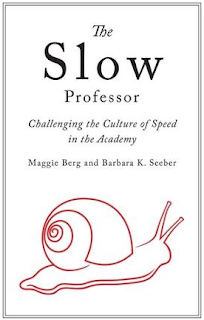

| The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy |

|

| Photo: Emma Rees |

|

| Photo:Times Higher Education |

George Harrison wrote the Beatles’ Here Comes The Sun holed up at Eric Clapton’s house, skiving a meeting with the executives at Apple Records. Despite its optimism, the song always sounds deeply melancholic to me because I can’t hear it without whooshing back through time to a Sunday evening years ago: I’m in my childhood home, in my flannelette nightie, freshly bathed, homework done and school shoes ready, watching the closing credits – at that time set to Harrison’s song – of the Holiday programme on the BBC. Despite all its wistful jingling and catchiness, that one song signalled the inescapable, stifling fact that the weekend was Over. To become an academic is to submit oneself to that Sunday evening feeling, seemingly in perpetuity.

The mental health of academics and administrators is at risk as never before. We might, on any given term-time Sunday evening (or, indeed, on any weekday night), prefer to be a skiver, like Harrison, but we find that the pressures of what my students term “adulting” are simply too great to hide from. The authors of The Slow Professor surely know that Sunday sensation too, and their plea is that, in the interests of self-care, we should all slow down and shift “our thinking from ‘what is wrong with us?’ to ‘what is wrong with the academic system?’”.

The Slow Food movement was initiated more than two decades ago by the activist Carlo Petrini. Local producers were celebrated over supermarket conglomerates, the detrimental effects of fast food on local communities were exposed, and a healthy kind of individuality thumbed its mindful nose at cultural homogeneity. Petrini’s work gained traction – sedately, of course – and in 2011 the Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman published his best-seller, Thinking, Fast and Slow, urging us to live “deliberate, effortful, and orderly” lives. Once it’s understood, the logic of the Slow Movement is irresistible. What Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber are doing in The Slow Professor is protesting against the “corporatization of the contemporary university”, and reminding us of a kind of “good” selfishness; theirs is a self-help book that recognises the fact that an institution can only ever be as healthy as the sum of its parts.

In their endeavour to “foster greater openness about the ways in which the corporate university affects our professional practice and well-being”, Berg and Seeber openly echo the tone and agenda of Stefan Collini’s What are Universities For?. And “well-being” ought to be a top priority for what the authors portray as a culture that “dismisses turning inwards and disavows emotion in pursuit of hyper-rational and economic goals”. Just last month, Times Higher Education ran a remarkable first-hand account of one academic’s experiences with mental illness. “In my own case,” wrote that anonymous contributor, “I know how vulnerable I am to feeling alone and unable to cope as I drown beneath a seemingly endless avalanche of work.”

This book is an intervention into precisely that “avalanche”; a mountain-rescue effort for the knackered academic. Its “Slow Professor manifesto” has three aims: “to alleviate work stress, preserve humanistic education, and resist the corporate university”. But it’s definitely not a joyless philosophy that the authors share: “We see our book as uncovering the secret life of the academic,” they write, “revealing not only her pains but also her pleasures.” They offer solutions, too, in addition to identifying what’s broken (they are writing from the perspective of members of the Canadian academy, which, as they present it, seems virtually indistinguishable from the British one). In critiquing those guides to time management that favour speeding through a punitive checklist over sitting in meaningful contemplation, they get it absolutely right: “It is not so much a matter of managing our time as it is of sustaining our focus in a culture that threatens it.”

Read more...

Additional resources

The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy

By Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber

University of Toronto Press, 128pp, £15.99

ISBN 9781442645561 and 663107 (e-book)

Published 20 May 2016

The authors

|

| Photo: Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber |

Maggie Berg, professor of English at Queen’s University, Kingston, was born in Portsmouth, Hampshire, and raised on Hayling Island. “My dad had a heart attack at the age of 43 and left my mum with five young children (I was the oldest). Although she had left school at 16 to become a hairdresser, Mum got herself a job with the Portsmouth Evening News and we kids helped to bring up each other. We were what is now called underprivileged. I was the first person in my family to go to university, and if it hadn’t been for the grants system at the time I would not have done so. Because of this background, I have never fitted comfortably in academia; it has left me with an awkward combination of gratitude and scepticism. However, I believe it has also made me a better teacher.”

She now lives in Kingston Ontario, “with Scott Wallis – who is a brilliant visual artist and a preparator in Queen’s University gallery – for 30 years. We are very different: I get up at 6am and go for a run; he stays at home smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. It works. Neither of us drives and we will never own a car. Our daughter Rebecca used to be annoyed by this, but now she is 26 she herself drives. Rebecca, who is the loveliest human being I could ever have imagined, is pursuing an MA in Counselling Psychology at the University of British Columbia. I asked her one day whether she would practice couples counselling on me and her dad; she was horrified and flatly refused.”

What is the wisest book she has read of late? “I have passed on, and sometimes made my students read, Tom Chatfield’s How to Thrive in the Digital Age, Sherry Turkle’s Reclaiming Conversation, and Dave Eggers’s novel The Circle. I realise just now that they have something in common: they urge us to consider that the very technologies that enhance our lives also, in the words of Chatfield, ‘have the potential to denude us of what it means to thrive as human beings’.”...

Her co-author, Barbara Seeber, professor of English at Brock University, St Catharines, Ontario, was born in Innsbruck in Austria, and lived there until she was 13, when her family moved to the West Coast of Canada.

“The slow food movement started in Italy but its principles are also cherished in Austria, so I grew up in a culture that insists on everyday pleasures and the conviviality of sharing a meal and conversation. I think that the immigrant experience has shaped me in some fundamental ways. It undoubtedly has enriched my perspective, but it also has led to feeling that I don’t quite fit in (both in Canada and in Europe).

“In terms of my work as a professor of English literature, being an immigrant also has had both positive and negative consequences: many academics suffer from the ‘imposter syndrome’, and working in your second language certainly intensifies that. But it also has given me the freedom that can come with approaching topics from the outside. For example, my primary area of research is Jane Austen and because I didn’t grow up hearing about Aunt Jane, I didn’t have preconceived ideas about her work.”

Seeber lives in St. Catharines, “a small city in the Niagara Peninsula (famed for its wine and its falls) near Toronto, Ontario. I am fortunate to share my house with two lovely companions: Georgie, a Shih Tzu, and Frida, a Chantilly cat, who are best friends. Before them, I lived with a very special cat named Darcy, named after the hero in Pride and Prejudice.”

If she could change one thing about the Canadian university sector, what would it be? “I wish that higher education would be tuition free. Higher education, like healthcare, is a public good.”

Read more...

Source: Times Higher Education